If you're shopping for a diamond, make sure you ask if it's a lab-grown diamond. Lab grown diamonds have the exact carbon structure as mined diamonds and are claimed to be indistinguishable from natural diamonds without testing equipment.

An expensive device developed by DeBeers for diamond dealers is an instrument which uses ultraviolet light to detect the difference between natural and lab grown diamonds. Lab grown diamonds will show a strong phosphorescent glow that is not common to natural diamonds.

Some say the development of lab-grown diamonds are exactly the same as mined diamonds. This statement is causing an upheaval in the jewelry industry.

Lab grown diamonds are promoted as ecologically progressive, however this has not been documented or proven. The lack of disclosures about what the waste byproducts are comprised of and the disposal procedures are a major environmental concern. We should be asking questions; how is this affecting our environment? Without this information how can lab grown diamonds be marketed as environmentally safe? With the current information regarding "applications for using water and the wastewater treatment" that are currently in developmental research, is it really ecological?

Lab grown diamonds are produced world wide; is not a futuristic idea. Produced in large to very small sizes by several private companies, including DeBeers and the Swarovski Group. One of the first lab grown diamonds made for commercial sales was a ten carat diamond by a Russian diamond lab in 2015.

The process starts by placing a small sliver of a mined natural diamond (called a seed) into a machine which will ultimately produce a larger (lab grown) diamond with the use of gases under high temperatures and pressure which aids in the binding of carbon atoms to the seed diamond to increase in size.

The cost difference of lab grown diamonds are currently less (expected to drop) than mined natural diamonds. This discounted amount will make it possible for more people to wear diamonds; comparable to the history of culturing pearls in the early twentieth century enabling more affordable pearls.

However, in my opinion, as more lab grown diamonds are produced worldwide the economics of 'supply and demand' will affect the overall pricing...similar to the cultured pearl industry years ago.

The term 'cultivated diamond' is used incorrectly to represent lab grown diamonds. For example, a cultured pearl is produced from oysters that are raised in 'farm' like conditions.

Diamonds do not grow; the molecular structure is expanding with additions of carbon molecules due to the properties of carbon in certain conditions that a lab is providing.

Make sure that you are aware of what you are purchasing. Lab grown should be fully disclosed to the buyer, engraved on the stone and sold with proper certification.

Russel Shor, from the Gemological Institute for America believes that the desire for mined natural diamonds will remain because "it comes from deep from Mother Earth...they are billions of years old, probably, the oldest thing we can buy."

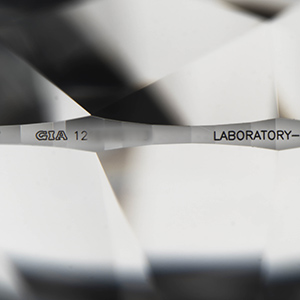

The abbreviations you should know when purchasing a diamond: The Gemological Institute of America (GIA) identifying stones that laboratories have produced using chemical vapor deposition (CVD) or High Pressure-High Temperature (HPHT).

I frequently post ongoing discussions and links to information about the pros and cons of lab grown diamonds vs. natural diamonds.

Janet Deleuse

UPDATED NEWS

Lab-Grown Diamond Grading Is Becoming Its Own Thing

By Rob Bates | September 27, 2024

At the JCK Show, I was with a group of people who work with lab-grown who were upset that a certain lab was supposedly lax in its lab-grown grading.

“It doesn’t matter,” one said. “It’s only lab-grown.”

I’ve complained in the past that some people in the lab-grown world sometimes devalue their product, and that’s a good example.

Of course the grades do matter, or at least they should. Otherwise, why have the report at all?

When lab-growns were first introduced, trade members disagreed on whether they should be graded along the standard GIA color and clarity scale, rather than the “category grades” originally favored by the GIA and eventually Lightbox. Today, that’s largely been settled. Almost all labs offer standard “Four C” grades for lab-grown diamonds.

But just because the scales are the same doesn’t mean the methods are.

As lab-grown prices have continued to fall, I’ve heard some complain that they are spending more on the diamond grading reports than on the actual diamond. And so lately, we’ve seen retailers and growers develop procedures to provide low-cost alternatives to grading them individually.

For example:

• In its prospectus, the International Gemological Institute (IGI) says it does “in-factory” grading for top growers, which sometimes involves the factory’s employees and equipment—a change from the traditional way independent labs have graded diamonds.

• De Beers’ Lightbox brand, whih did not grade its diamonds when it premiered, now issues “verification” reports for its diamonds. The GIA does “batch verification” checks for its highest-quality stones.

• Then there’s the GDTO, which issues reports based on retailer “quality controls,” and argues that labs shouldn’t look at every lab-grown stone individually.

They “really shouldn’t be certified in the way mined diamonds are certified,” David Sherwood, CEO of Daniel’s Jewelers, and a member of the GDTO’s advisory board, “If you’re pulling something out of the earth, you need to send it to a third party. You manufacture something to certain specifications, you shouldn’t send it to a third-party laboratory….

“What is the [grading] lab actually doing? They’re telling me that something is a VS1 when it was designed to be a VS1, quality-controlled to be a VS1, and the retailer agreed [through its quality controls] it’s a VS1. I don’t need [a lab to tell me] that.”

So what we have is an industry that’s using the same grading scale, but is sometimes using different methods to get those grades.

Given the economics here, that’s understandable. As long as it’s done honestly, that’s fine. But there must be transparency as well. Consumers need to know when a grade is derived differently from the norm. (Lightbox, for instance, notes the method behind its verification reports.)

If a shopper is presented with a third-party grading report—or something that’s represented as a third-party report—they might reasonably assume that (a) each diamond will be individually examined, and (b) the examination is done by a neutral arbiter. That’s how grading has traditionally worked.

If a diamond is being graded by the employees of the company that manufactures it, or is subject to quality control rather than individual identification, the consumer should know that. They may not understand all the possible implications of these deviations from the norm, but they shouldn’t be kept in the dark about them.

I’ve argued that the lab-grown diamond industry should embrace the reality that it’s a new industry and veer away from the outdated and extremely complicated 70-year-old GIA diamond grading scale. The sector could even develop its own quality measurement system, with tech tools, that would be far more scientific than what we have now. But as long as the lab-grown industry is sticking with the tried-and-true grading scale, many people will assume that it’s using tried-and-true grading methods. And if not, it should at least let people know.

Element Six Using Synthetic Diamonds to Manage “Forever Chemicals"

Element Six (E6), the De Beers subsidiary that produces synthetic diamonds for industrial purposes, has joined forces with Lummus Technology to create a diamond-based solution for the health issues associated with so-called forever chemicals: perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS).

The synthetic fluorinated organic compounds known as PFAS have been widely used in industrial applications and consumer products since the 1930s. They are often referred to as forever chemicals because they do not break down naturally in the environment, and are resistant to grease, oil, water, and heat. At high exposures, they can cause serious health problems, including cancer, decreased immunity, and infertility.

This partnership marries Element Six’s boron-doped diamond tech with Lummus’ solution for water and wastewater treatment. The two companies have tested their combined technologies, which resulted in successful destruction of certain PFAS.

A statement said that Lummus and Element Six already are making progress in developing real-life applications for this technology.

In June, Element Six announced it was working with Orbray to develop the world’s highest quality wafer-scale synthetic diamonds.

By Rob Bates | July 31, 2024. JCK

U.K. Lab-Grown Diamond Ruling Shows Why Words Matter

By Rob Bates | April 19, 2024

Last week, the U.K.’s Advertising Standards Agency (ASA), in response to a complaint from the Natural Diamond Council (NDC), ruled that U.K. lab-grown diamond brand Skydiamond must change the language in its advertising, which has described its products as “mined from the sky.”

“None of its ads included an explicit qualification that Skydiamonds were synthetic, laboratory-created, or similar,” the ASA said in its ruling. “Consumers could go through the entire process of buying a Skydiamond, from homepage to completion of the purchase, without any explicit mention that the diamond was synthetic.”

Skydiamond has said it will appeal, posting on LinkedIn: “The complaint from the NDC (and no one else) claims we were not clear enough that our beautiful stones were man-made and customers could be deceived into thinking we were dug from the earth not made from the sky. Apparently, our very name is not clear enough.…

“Not all lab diamonds are created equally!… There is a spectrum of how these are created, from mass production using cheap power and commercial gas, to bespoke batches created from renewable energy, to ours, uniquely produced right here in Britain using only four ingredients form the sky.”

Even if one agrees that Skydiamonds aren’t the same as other lab-grown diamonds, they are produced using chemical vapor deposition—which is the method that creates other lab diamonds. The ingredients may be different, but there’s no reason Skydiamonds shouldn’t be called “lab-grown.”

And while the company asserted in the LinkedIn post that its name is “clear enough,” it said in its submission to the ASA that such phrases as “mined from the sky” and “world’s rarest” were “obvious exaggerations or puffery, especially in the context of the ads and/or the qualifying information. They would not be taken literally by an average consumer and did not materially mislead.”

It’s certainly possible that consumers may believe that Skydiamond’s gems literally came from the sky. After all, diamonds have been found in meteorites and on other planets. And space mining is a real thing.

(One other comment: Skydiamond’s introductory email to consumers notes that “our diamonds are carbon-negative by design, making them the cleanest diamonds on planet Earth, as validated by Imperial College London.” Skydiamond hired Imperial College to study its diamonds’ impact. The ASA’s guidelines say “commercial relationships must be disclosed up front.”)

This British case is just one example of how the industry is still squabbling over lab-grown nomenclature, six years after the lab-grown boom began in earnest. Recently, I received an angry email from the CEO of a lab-grown company about my use of the word “synthetics” in the fifth paragraph of this story. This person claimed the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) prohibited the word’s use, which it expressly did not; the FTC even used the word “synthetic” in a 2021 blog post.

I’ve received other complaints over my use of “lab-grown,” with some natural diamond partisans arguing that “factory-grown” or “man-made” would be more appropriate. “Man-made” is a decent descriptor, one the FTC has itself used. But it’s not gender-neutral, and technically the stones are machine-made. I agree “factory-grown” is probably more accurate than “lab-grown,” but the latter term has now been used for years. It’s government-approved, and well-known enough that its use has spread to products like meat and plants. (There’s even talk of “lab-grown babies.”) I think it’s fine.

The bigger problem here is that no one has come up with a truly great term for lab-grown diamonds. (On our podcast, Tom Chatham recalled that his father, Carroll, hired a linguist to come up with the right words for his gems. Eventually a judge okayed “Chatham-created.”)

Remember, the government’s rules don’t just protect the natural diamond industry (and consumers), they protect everyone. For years, many simulant sellers have called their products “lab-grown diamonds,” which they are not. The only thing now preventing more companies from doing so is the threat of government intervention.

Earlier this year, France decreed that only “synthetic” can be used to described lab-growns, which I find silly and restrictive. Otherwise, current U.S. and U.K. regulations are reasonable, make sense, and are not that hard to comply with. We may quibble with certain aspects of them, but hundreds of companies follow them every day. When some decide not to, it puts the ones that do at a disadvantage. They shouldn’t be surprised when people complain.

France Says Diamond Growers Must Stick to “Synthetic”

French authorities have ruled that lab-grown diamond sellers can only use the word synthetic to describe their product.

A 2002 decree lists synthetic as the only acceptable qualifier for stones “whose physical, chemical properties and crystal structure correspond essentially to those of the natural stones that they copy.”

In 2022, a diamond manufacturer asked France’s Ministry of the Economy, Finance, and Industrial and Digital Sovereignty to modify the rule to allow use of the term laboratory-created. But last October, following consultations with the trade, the ministry decided things should stay as is.

“Many of you (nearly forty, including the professional federations) responded to [our] questionnaire, and we thank you for that,” said a ministry email sent to those who commented. “An analysis of the replies received shows that a majority of players are in favor of maintaining the [2002] decree.”

French jewelry organization UFBJOP was among the parties that submitted input, contending that laboratory-grown and laboratory-created have “no acceptable French-language translations.” By contrast, it called synthetic a “clear term, understandable by the consumer.”

“[A survey of] more than 1,000 French people, aged 25 and over, revealed that 83% of French people were able to give a definition to synthetic diamonds, characterizing them mainly as an artificial stone,” UFBJOP said. “90% of those questioned understood that these stones are not extracted from the Earth.”

It further noted that international Customs authorities require manufactured diamonds to be labeled synthetic.

Despite the existing decree, the term lab-grown has often been used by French jewelers that sell synthetic gems, including Courbet and LVMH-owned FRED. The two companies did not return a request for comment.

The French government’s stance on this issue differs from the U.S. Federal Trade Commission’s. In 2018, the FTC removed synthetic from its list of recommended terms for lab-grown diamonds, saying consumers might mistakenly believe that lab-grown diamonds are non-diamond simulants akin to cubic zirconia. However, contrary to some assertions, the agency did not disallow synthetic—and, in fact, used the word in a 2021 blog post about shopping for gemstones.

Is That Inscription Real? Reports of Mislabeled Lab-Growns Increase

By Rob Bates | January 10, 2024

Need grows for lab-grown diamond detection

Rob and Vic’s conversation shifts to an unsettling trend involving people attempting to pass off lab-grown diamonds as natural. With the price gap between the two markets widening, disguising lab-grown diamonds as natural ones becomes more tempting, so “I think it’s possible these incidents will increase,” Rob says. Such mislabeling is illegal, he warns.

After two gemological labs found lab-grown diamonds with fraudulent inscriptions misidentifying the stones as natural, trade groups have introduced same-day services to verify a diamond’s inscription and origin.

On Sunday, the Diamond Manufacturers and Importers Association (DMIA) announced that it had installed four diamond identification machines at its New York City offices. Group members can use the devices free of charge, by appointment only.

The DMIA has also begun offering a same-day service with the International Gemological Institute (IGI) that allows for quick identification of individual diamonds as well as parcels.

GIA, meanwhile, is rolling out a same-day service meant to verify whether a diamond’s inscription corresponds to the actual stone. The service, which will initially be free, is expected to start next week, first in New York City, then in other markets. It will be open to walk-in clients, who can expect a 15-minute wait for one loose stone. (Mounted stones can be checked but will require more time.)

The news comes amid increasing reports of fraudsters marking lab-grown diamonds with counterfeit inscriptions that correspond to previously graded natural gems.

Earlier this month, IGI reported that a 6.01 ct. lab-grown pear-shape had been submitted with a fake GIA inscription (pictured at top) identifying it as a natural diamond.

While some took the announcement to imply that GIA had misidentified the diamond’s origin, an IGI spokesperson tells JCK that the inscription was a counterfeit not issued by GIA. The inscription did include a genuine report number that corresponded to a natural diamond GIA had graded.

IGI’s spokesperson says the “client submitted the stone [to IGI] for screening, to determine whether it was natural or not.”

Last week’s IGI release said that the diamond’s “carat weight, physical spread, and primary qualities matched the natural diamond’s online data.” However, subsequent analysis revealed a carbon inclusion in place of the feather indicated by GIA, as well as a mismatch in reported depth. The IGI cautioned that “such discrepancies could go unnoticed outside of a laboratory, particularly once the stone is set into a piece of jewelry.”

The lab isn’t releasing the name of the client, and added that the source of the fake inscription is “unknown.” The spokesperson says, “All IGI clients are subject to know-your-customer measures and compliance with our terms and conditions.”

In December, Italian lab Gem-Tech said it had spotted three synthetic diamonds with fake inscriptions that falsely identified them as GIA-graded natural diamonds.

Again, all three diamonds had the same weight and similar characteristics to the diamonds matching the fake inscriptions. But Gem-Tech detected differences in the diamonds’ reported proportions and fluorescence, and later confirmed the stones were grown with chemical vapor deposition.

“It would not be the first time that malicious individuals have legitimately obtained reprints of authentic reports and paired them with stones other than those described,” said the lab in a statement. “Furthermore, cloning a document by forging the type of paper backing and authentication systems is not particularly complex. The technology to laser-engrave any logo is now available to many, making it less secure.”

Gem-Tech noted that “new, more sophisticated systems are appearing on the market” that “are virtually impossible to counterfeit because they are based on laser inscription beneath the surface of the diamond.”

GIA warned last year that it had seen a number of diamonds with fake inscriptions.

This Ban will have an impact on the Lab Grown Diamond Industry.

EU Banning Descriptors “Eco,” “Climate Neutral,” “Carbon Neutral”

By Rob Bates | September 22, 2023

European Union legislators have struck a deal for new rules that will ban most companies from using widely used eco-descriptors like environmentally friendly, eco, climate neutral, and carbon neutral.

The new rules still have to receive approval from the full European Parliament and Council. Those bodies are expected to vote in November. If the rules are approved, member countries will have until 2026 to enact the guidance.

The deal calls for:

-A ban on generic environmental claims if the trader cannot demonstrate an excellent environmental performance.

– A ban on sustainability labels that are not based on certification schemes or established by public authorities.

– A ban on claims based on emissions-offsetting schemes, which are typically called carbon neutral or climate neutral.

– A stricter set of rules for claims of future environmental performance, which will be allowed only if they are accompanied by a realistic implementation plan and feasible targets. They must also be reviewed by independent third-party experts, and their findings will be made available to consumers.

The news comes as the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) is overhauling its Green Guides, which dictate how U.S. marketers should communicate environmental claims. The Jewelers Vigilance Committee and other industry players recently submitted suggestions on how the guides should be modified.

EU consumer advocates hailed the new rules.

“Generic environmental claims are popping up everywhere, from food to textiles,” Ursula Pachl, deputy director of the European Consumer Organization (BEUC), in a statement. “Consumers end up lost in a jungle of green claims with no clue about which ones are trustworthy. Thankfully, the new rules are putting some order in the green claims’ chaos.

“Companies will have to explain why a product is environmentally friendly. This is crucial if we are to guide consumers to make more sustainable consumption choices.”

Pachl called the ban on claims about carbon neutrality “great news for consumers.” The new language goes further than the EU’s original proposal, which allowed the terms but called for increased transparency around electrical use and carbon offsets.

“Carbon neutral claims are greenwashing, plain and simple,” Pachl said. “It’s a smoke screen giving the impression companies are taking serious action on their climate impact.”

In 2020 the European Commission assessed 150 business environmental claims and found that 53% of them contained “vague, misleading, or unfounded” information. Another survey found that 40% of eco-claims made by EU businesses were likely misleading.

The Long History of Stabilizing Lab-Grown Diamond Prices

Why Not All Lab-Grown Diamonds Are Created Equal

By Victoria Gomelsky | March 13, 2023

“We owe it to the public to have more transparency about lab-grown diamonds,” Reinsmith said. “We should cease referring to them as identical, with differences only seen with special tools. If you’re an independent jeweler who recently started selling lab-grown, you likely built your business on reputation. You owe it to your customers to get educated on what the quality characteristics are beyond the 4Cs."

Imagine two round brilliant-cut diamonds displayed side by side. Each is 1 ct. in size, F color, VS2 clarity. One is a natural, mined diamond and the other is lab-grown.

Most retailers have been taught that beyond their disparate origins, the diamonds are chemically, optically, and physically identical, and that’s the message they’ve conveyed to consumers.

“For years, the trade has repeated these sentiments: that lab and natural diamonds are indistinguishable from each other,” says Lindsay Reinsmith, chief operating officer and director of sales at Ada Diamonds, a lab-grown, direct-to-consumer diamond brand based in San Francisco.

“We’re seeing so many more reductive claims that this is an indistinguishable product and that’s not the case,” adds Jason Payne, Reinsmith’s husband and CEO of Ada Diamonds.

The potential structural and crystal differences between lab-grown and natural diamonds, as well as between lab-growns in general, go well beyond the 4Cs (cut, color, clarity, and carat size), and can often be seen with the naked eye. That was the gist of an hour-long presentation that Reinsmith and Payne gave at GIA headquarters in Carlsbad, Calif., on March 1 as part of the institute’s monthly guest speaker series.

“I look at lab diamonds all day,” Reinsmith tells JCK. “The year 2019 was a big turning point. We started to see a lot more material. We’d ask to inspect stones for our inventory and we started to see a lore more variants beyond the 4Cs in our office. And we started to have conversations with growers.”

Much of what Reinsmith and Payne began seeing were lab diamonds grown via chemical vapor deposition (CVD) that were tinged with brown or gray colors, or featured signs of strain and striation—lending the stones a streaky and blurry appearance, respectively.

In diamonds grown by high-pressure, high-temperature (HPHT) presses, some of the telltale signs of poor-quality growth that Reinsmith and Payne noted were stones tinged with blue or gray, as well as those that had phosphoresced.

The couple explained these crystal defects as the intentional byproducts of growing processes designed to speed product to market at the expense of quality.

“In the beginning, lab diamond growers sought to create super high-purity crystals that rivaled some of the best natural diamonds,” Reinsmith said during the presentation. “Then, in the last few years, interest exploded. Aspirational players [entered the market], many using disadvantaged technology. A lot had no business growing diamonds.

“The problem was exacerbated during Covid,” she added. “Diamond mining stayed shut longer than diamond growing. Cutters needed rough to cut and this has incentivized a market that encourages producing as much and as fast as possible for the lowest cost possible.”

As growers around the world sought to increase their output, yet lacked the finances to increase their capital investments, they began taking shortcuts, said Reinsmith.

“You accelerate your growth cycle, you use and reuse cheap materials, you introduce masking materials,” she said “Lab-growns got faster and cheaper to produce, but not better.”

Payne made clear that growing problems often start with seeds. “There is no such thing as a perfect seed,” he said. “Seed quality defines diamond quality. The more faults, the blurrier the diamonds.

“Seeds deteriorate with each use,” he added. “So every time you use a seed, and start and stop your CVD reactor, the quality of the seed decays. You recycle them and they get poorer in quality. The challenge for CVD growers is to procure good quality seeds.”

The upshot of these market dynamics is two-fold: One, there’s been a glut of lab-grown material, particularly in the 2 to 3 ct. range. And two: The market is bifurcating into two segments, one populated by upscale producers who take time growing their diamonds and charge a premium as a result, and budget producers who prioritize fast, cheap goods.

Reinsmith and Payne said they expect greater industry consolidation, as poor-quality growers begin going out of business, and, in the worst-case scenario, a consumer confidence crisis that stands to disrupt the entire lab-grown diamond trade.

No, Lab-Grown Diamonds Are Not “Mining-Free”

By Rob Bates | February 08, 2023

This year, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) will start revising its “Green Guides,” which lay out rules for environmental marketing claims.

The Jewelers Vigilance Committee (JVC) is asking the industry for suggestions for how the Green Guides should handle jewelry. (JVC’s suggestion form is here.)

Here’s one relatively small—but irritating—issue that I hope will be considered.

The FTC should not allow—or, at the very least, it should place strict parameters on—terms such as “mining-free,” “created without mining,” and “no mining.” These descriptors are frequently used for lab-grown diamonds. Examples can be seen here, here, here, here, and here.

From what I understand, the FTC judges claims and descriptions on two main criteria. First, they have to be true. (Obviously.) Second, they have to clearly communicate the nature of the product.

So, for example, the term “aboveground diamonds” might be technically accurate, but FTC lawyers say it doesn’t properly communicate the diamond’s lab-grown origin. (After all, some natural diamonds are found above ground.)

A descriptor such as “mining-free” does fulfill the second criteria: It clearly communicates the diamonds’ lab-grown origin. The problem is, lab-grown diamonds aren’t mining-free.

“Mining-free” implies there was no mining involved in the diamonds’ production. But very few products in this world can be considered truly mining-free. The iMac I’m typing this on certainly isn’t. Mined materials will also be needed to produce green technology. However you feel about mining—and it’s a sector with plenty of bad as well as good—its products surround us daily. Without it, we couldn’t get much done.

Manufacturing high-pressure high-temperature (HPHT) diamonds requires graphite. Producing lab-grown diamonds with the chemical vapor deposition (CVD) method requires high-purity methane and hydrogen. The methane is generally sourced from oil, gas, and coal mining.

“Methane mainly comes from the ground,” says David Hardy, founder of Bringdiamonds.com, a diamond grower. “So does graphite.… Even the equipment used has metals, and they don’t come from the air either.”

Ryan Shearman, cofounder and chief alchemist of Aether Diamonds, which converts carbon dioxide captured from the air into methane to create lab-grown gems, asserts that “there’s no real way to source methane responsibly. It’s either coming from crude oil production or it’s coming from fracking.”

He says new ways of generating methane are starting to emerge—including from biogenic sources (i.e., farm animals)—but there aren’t currently established supply chains for that. read entire article

Lab-Grown Diamonds Setting New Size Records

JCK. By Rob Bates | February 01, 2022

The International Gemological Institute (IGI) and the Gemological Institute of America (GIA) labs have recently examined the largest lab-grown diamonds they have ever seen grown with the high-pressure, high-temperature (HPHT) and chemical vapor deposition (CVD) methods.

In January, the IGI announced it had seen a record-setting lab-grown blue crystal piece of rough (shown at top), which weighs 150.42 cts. and measures 28.55 mm x 28.25 mm x 22.53 mm. This is believed to be the largest lab-grown diamond ever produced.

It also saw a second gray crystal weighing 141.58 cts. that measures 28.9 mm x 28.5 mm x 20.75 mm.

“The acceleration of technology in the lab-grown diamond sector is significant,” said IGI senior director of education John Pollard in a statement. “In addition to record-setting weights, they’re type IIb crystals, a semiconducting category associated with diamond-based electronics.”

Both diamonds were grown in Ukraine with HPHT by Alkor-D, a subsidiary of Meylor Global. Meylor had set the prior record for the world’s largest lab-grown diamond, which weighed 115 carats.

At last year’s JCK Las Vegas show, Meylor Global CEO Yuliya Kusher told JCK her company was working on a 200 carat diamond.

“I don’t think CVD can do that,” she said. She added that while most Chinese producers use HPHT, “they are making a lot of melee, [not even] 1 ct.”

Meylor Global is the official distributor of diamonds created by New Diamond Technology, the grower based in Russia known for producing record-setting diamonds. It is owned by Ukrainian national Timur Mindich.

In addition, the GIA recently examined the largest known polished lab-grown diamond it has ever seen produced by CVD.

The 16.41 ct. princess-cut diamond was grown with the CVD method by Shanghai Zhengshi Technology Co., which has been working on CVD technology since 2002.

GIA Sees Spike in Synthetics Fraud

May 18, 2021 7:29 AM By Rapaport News

RAPAPORT... The Gemological Institute of America (GIA) has seen a rise in submissions of lab-grown diamonds with counterfeit inscriptions that make the stones appear natural.

Clients using the GIA’s update or verification services are increasingly sending in goods that prove to be synthetic, the organization said Monday. These stones have falsified girdle engravings that reference a genuine natural-diamond report number, while most have almost identical measurements and weights to the natural diamonds they mimic.

In a recent case, someone submitted a 3.075-carat, H-color, VVS2-clarity, triple-Ex, lab-grown diamond to GIA Antwerp for an update. The stone carried a report for a 3.078-carat, G-color, internally flawless, triple-Ex natural diamond. The synthetic stone’s real-life dimensions were within hundredths of millimeters of the measurements in the natural-diamond report, the GIA noted.

“This unfortunate situation demonstrates why it is important, especially in any transaction where the buyer does not have a trusted relationship with the seller, to have the diamond-grading report updated before completing a purchase,” said Tom Moses, the GIA’s executive vice president and chief laboratory and research officer.

The GIA blotted out the counterfeit inscription and inscribed a report number for a new certificate that it issued, adding the term “laboratory-grown” on the girdle, as is its practice.

In February, the institute reported that it had received a number of lab-grown or treated stones carrying natural reports and fake inscriptions.

Watchdog: Diamond Foundry Ads Could Confuse Consumers

By Rob Bates | April 01, 2021

BBB National Programs’ National Advertising Division (NAD) has recommended that Diamond Foundry modify some of its advertising, to better communicate that its diamonds were grown in a lab.

Diamond Foundry—which just disclosed it has raised $200 million in funding in an SEC filing—said it will comply with the recommendations. The Santa Clara, Calif.–based company manufactures and sells lab-grown diamonds through an office in Dubai, United Arab Emirates, and via e-tail subsidiary Vrai.

In its decision, released March 30, the NAD, responding to a complaint from the Natural Diamond Council (NDC), found that certain Diamond Foundry and Vrai ads could “create confusion” about the origin of their diamonds.

In particular, the NAD took issue with some of Diamond Foundry’s and Vrai’s social media ads and posts, which label its products as “diamonds” without accompanying modifiers or descriptors.

The NAD advised Diamond Foundry to make “clear and conspicuous disclosures [about the diamonds’ origin] immediately preceding, with equal conspicuousness, the word diamond,” as prescribed by the Federal Trade Commission’s Guides for the Jewelry Industry.

It also recommended that Diamond Foundry and Vrai not describe products as “created diamonds,” “diamonds created aboveground,” “sustainably created,” “sustainably grown,” and “world positive,” as those terms “do not sufficiently communicate that the diamonds are laboratory-grown.”

The NAD acknowledged that the Diamond Foundry and Vrai sites feature “clear messaging” about their diamonds’ origin, citing the slogan “Just diamond. No mining.” Yet it warned that consumers “may not be exposed to that general messaging.”

The group also expressed concern about a webpage where Diamond Foundry called its diamonds “real.”

The company should “discontinue social media claims that its LGDs are ‘real’ diamonds or modify the claims to make clear that its LGDs are not mined diamonds,” the NAD said. “[W]ithout context explaining that ‘real’ diamonds are created in a laboratory and not mined, consumers may reasonably take away the unsupported message that Diamond Foundry’s diamonds are mined diamonds.”

The NAD did swat down the NDC’s objection to the term Diamond Foundry–created. That term, it said, is “not misleading.”

It’s somewhat surprising that NDC objected to that particular phrase, as [manufacturer name]-created is one of three descriptors the FTC recommends in its Guides. The other two are laboratory-grown and laboratory-created.

The NAD noted that nothing in its decision precludes Diamond Foundry from using the phrase diamonds created aboveground if it appears in a context that clearly discloses the diamonds are man-made. It can also use the phrase world positive “if it is tied to a specific benefit or feature of Diamond Foundry’s LGDs, when accurately disclosing the diamonds’ origin,” it said.

Diamond Foundry said it will heed the NAD’s counsel “out of respect for the self-regulatory process.” It also told the NAD it disagreed with certain aspects of its decision.

The company added: “We are pleased with NAD’s observation that ‘Diamond Foundry’s advertising on its website is replete with clear messaging as to the man-made nature of its diamonds and often plainly contrasts its products with mined diamonds…in advertising for both the Diamond Foundry manufacturing brand and the Vrai retail brand.’ ”

This is not the first time Diamond Foundry has faced controversies about its advertising.

In 2019, the FTC sent warning letters to Diamond Foundry and seven other companies about how they described their diamonds.

“The FTC staff is concerned that some of your advertising fails to conform to the Jewelry Guides and therefore may deceive consumers,” read its letter to Diamond Foundry. “The term aboveground real diamonds does not clearly and conspicuously disclose that the diamonds are laboratory-created.”

Prior to that, the Jewelers Vigilance Committee complained of fuzzy descriptors in Diamond Foundry’s collaborations with Barneys New York and Jennifer Fisher.

“There have been prior warnings,” says JVC president and CEO Tiffany Stevens. “In the digital environment we’re in, it’s particularly important that advertising be truthful and accurate. We know there is continued interest from the FTC in looking at advertising practices in the jewelry sector.”

David Kellie, CEO of the Natural Diamond Council, which has said it is taking a less confrontational stance toward lab-grown gems, tells JCK that while the group’s focus remains on promoting natural diamonds, it does seek “to protect the integrity of our industry on behalf of the businesses and tens of millions of employees, their families, and communities whose livelihoods depend upon diamonds and diamond jewelry. Unfortunately, this means that from time to time we need to raise issues of concern and seek resolution and remedy through appropriate channels.”

In related news, Diamond Foundry is being sued in Canadian court by Ofer Mizrahi Diamonds (OM), for allegedly poaching its people and stealing its secrets.

The complaint, filed March 16 in the Supreme Court of British Columbia, charged that, in August 2019, one of OM’s Canadian employees left the company for a position as vice president of Diamond Foundry. Four other OM employees subsequently joined her, it said.

According to the complaint, the move may have violated the woman’s employee agreement, which forbade her from accepting a job with a competitor, or inducing other employees to leave for six months after her departure. OM is part owner of Green Rocks, a lab-grown diamond company.

The complaint alleged that the ex-employees gave Diamond Foundry access to OM’s customer database as well as other confidential information. It charged breach of contract, unjust enrichment, and other counts, and seeks $5 million in damages.

Diamond Foundry tells JCK, “We’re proud of our sales team and while they may be the envy of others, our attorneys do not see any merit in the claims made.”

GIA Finds Fake Inscriptions On Diamonds

GIA’s grading lab recently detected “a number” of diamonds that had counterfeit GIA inscriptions on their girdles.

“This is not the first time we have seen this,” says spokesperson Stephen Morisseau. “But recently we have seen a number of stones with fake inscriptions.”

According to GIA, the diamonds were submitted for updated reports or verification services, but their qualities did not match the GIA reports associated with the inscriptions, which turned out to be counterfeit. The diamonds in question were either lab-grown or treated naturals; the reports connected to the fake inscriptions were for non-treated or natural diamonds.

In one example, a diamond was submitted with an inscription that indicated it was a 1.5 ct. natural diamond, E VVS2, type I, with an excellent cut grade. In actuality, the diamond was lab-grown, 1.51 cts., D VVS2, type IIa, with a very good cut grade.

“It [was] clear that these are two different diamonds,” the GIA said in a statement, even if “the weights and grading parameters of the original and newly submitted diamonds were close to each other.”

In these cases, the GIA overwrote the counterfeit inscription with an X, and inscribed the girdle with a new report number and, when applicable, the word lab-grown. It then issued a new, accurate report, noting the diamond’s treatment or non-natural origin.

So who is doing this? “Obviously, we know who submitted them,” says Morisseau. “But we are not making any statement about patterns, or types of stones, or [submission] locations.”

The statement added: “These instances of attempted fraud highlight why it is important, especially in any transaction where the buyer does not have a trusted relationship with the seller, to have the diamond grading report updated prior to completing a purchase.”

The statement noted that GIA’s client agreement gives it the option of notifying the “submitting client, law enforcement, and the public” about any instance of purported fraud. However, Morisseau says he cannot comment on how GIA is handling these instances.

It is a violation of the Federal Trade Commission’s Guides for the Jewelry Industry to pass off a lab-grown diamond as natural without clearly and conspicuously disclosing its origin. LINK to article

By: Rob Bates

|

NOVEMBER 19, 2020

WWD. Online Magazine Says

● Consumers and retailers seeking a value ratio and eco-friendliness are creating momentum for lab-grown stones, despite pushback from the diamond mining industry.

BY MISTY WHITE SIDELL,

Lab-grown diamonds continue to grow in popularity and awareness with consumers, according to new research. A report issued today by MVI Marketing says the cultivated stones are “poised to reach mass market status,” with more than 50 percent of independent jewelers in the U.S. expected to stock the stones in time for this holiday season.

This information comes despite the world’s top diamond mining firms’ efforts this year to promote natural diamonds through their joint lobbyist venture, the Natural Diamond Council. MVI Marketing’s report notes that general household awareness of lab-grown stones now stands at about 80 percent, up from 58 percent in 2018. The stones are poised to take additional market share in the coming months — particularly for their value ratio. “Consumers are most drawn to the size-to-value equation. Shopping within a budget, as most consumers do, when shown both mined and lab-grown diamonds, the bigger stone of the same quality in lab-grown diamond appears to be the winning proposition for most couples getting engaged.

Eco-friendliness is the icing on their diamond cake, especially for Millennials,” said Marty Hurwitz, chief executive officer of MVI Marketing, which has tracked lab-grown diamonds since 2004. Lab-grown diamonds offer consumers an average of 30 percent value for price and size, compared with natural stones, the survey said. Hurwitz added that 95 percent of lab-grown diamond retailers report better profit margins with lab stones than natural diamonds (between 16 to 40-plus percent) — a crucial source of revenue during this challenging economic period.

While some jewelers may feel attached to the romantic notion of naturally sourced stones, Hurwitz advised otherwise. “Jewelers have to make a profit and hanging onto one product that sells love may not be a good idea. Rather retailers should present consumers with a choice of both mined and lab-grown diamonds, and make money with the products consumers see as love,” he said. The stones are most popular with younger consumers (aged 25 to 35) whose response to lab grown diamonds was “overwhelmingly positive,” while other age groups were more skeptical — with 46- to 55-year-olds having the lowest opinion of the stones.

Hurwitz advised jewelers to pay more attention to the younger age group’s opinions, since they are the market that is getting engaged. The survey noted a fledging interest in larger lab stones, measuring from two to three carats in weight. As told to WWD in October, Lightbox — De Beers’ lab diamond subsidiary — is now in the process of developing larger lab stones. Currently, the company only offers lab diamonds up to one carat in weight.

Lightbox’s new Oregon manufacturing facility, opened last month, is ramping up production — expected to produce 200,000 carats of polished diamonds a year. The company has teamed with Blue Nile — among the U.S.’ largest online jewelry stores — on distribution of its lab diamonds, marking one of the biggest retailers to include lab grown stones in its assortment. “We have been thinking pretty hard about [lab diamonds], talking to consumers about how they could or would fit into our brand and our merchandise strategy,” said Blue Nile ceo Sean Kell. “We decided that the trend is not going away — these are beautiful stones and the quality and availability of stones has improved dramatically, even over the last year or so. It made sense to us to dip our toe into market.”

WWD online article

Interview With WD Lab Grown CEO Sue Rechner

You are working to have your diamonds certified as sustainably produced by SCS Global Systems. [Note: This standard can be seen here and is now open to both natural and lab-grown diamonds.]

This sustainability certification is near and dear to my heart. It’s one of the reasons I stepped into this role, because I thought it could be a game changer for the overall diamond category. WD is on track to be the first company certified through SCS, which is a milestone, not just for our brand but also the entire industry, because that is what consumers expect. They vote with their wallet, and people want to know what they’re buying, where it comes from, and they understand the impact that it has on the world. So this is a major accomplishment for us.

Your previous CEO admitted that growing diamonds takes a large amount of energy. How has that affected your ability to be certified as sustainable?

We were evaluated under 15 core environmental impact categories that SCS has as a baseline. We’re working toward zero impact for all environmental and human health impact. We’re working toward achieving full climate neutrality. Do we use a lot of electricity? Yes. But, there are ways to improve. Once you judge yourself and once you give yourself a report card, you then have the ability to start doing things to improve the impacts that you’re having on the world. So the first thing is to give yourself a baseline, and that was done by SCS. They have exhaustively audited our facility, our supply chain, and our chain of custody. We are going to use the most advanced empirical testing technology available to provide provenance signature and gem identification matching, so we will establish 99% accuracy for the provenance of our diamond.

It’s not been easy. We have been working on this since, I believe, January. We’ve opened our books and opened our kimono to say, these are all the things that we’re doing, tell us how we can get better. That’s where it all starts and that’s what consumers want to hear. They want to hear that companies are being transparent about who they are, how they operate, and the impact they have on the world. entire article....

WD Lab Grown Signs 2 Patent Sublicensing Agreements

JEWELRY NEWS

Diamonds Are Being Called Natural Diamonds Now

Find out why June 19, 2020

One of the most well-known contemporary examples of a nickname entering the official jewelry vocabulary is when diamond line bracelets became tennis bracelets after Chris Evert dropped hers on the court while playing in the 1978 U.S. Open.

During the 1920s, rectangular shaped diamonds were designated as emerald-cut diamonds because the shape was a popular one for emeralds. It was also a new shape for diamonds that was achieved with advancements in diamond cutting. The name “emerald-cut diamond” has stuck despite the fact that it feels like a misnomer.

It’s not a coincidence that both of these examples are related to diamonds. The gem has gone through more changes in terminology over the years than any other area in the jewelry field. One reason for the steady evolution stems from the fact that diamonds are such an important ingredient in fine jewelry. “Diamonds are the common denominator of jewelry,” is how Nicola Bulgari succinctly explained it to me when I was interviewing him for my book Diamonds: A Century of Spectacular.

One of the watershed moments in modern diamond terminology happened in the early 1940s when the 4Cs concept was launched by the Gemological Institute of America’s founder Robert M. Shipley. The master gemologist came up with the mnemonic aid to help people have a better understanding of the qualities a gem is judged by: cut, clarity, color and carat weight. Needless to say, the idea caught on.

Diamond grading as we know it today was another program invented by the GIA. In 1953, a team of gemologists lead by Richard T. Liddicoat came up with a color scale for diamonds ranging from D to Z. People often wonder why the best color grade is “D” as opposed to “A.” The answer relates to the color scale it replaced. Gems were once unsystematically graded A, AA and AAA. The new set of letters beginning with D moved far away from that. Somewhat counterintuitively, the thinking at the GIA was to begin with a letter for the best quality that had a negative connotation so it wouldn’t be misused.

Today, diamond terminology is being updated again. Diamonds mined from the earth have been rechristened natural diamonds. Promotion of the name change is being spearheaded by the Natural Diamond Council, a group formerly known as the Diamond Producers Association (DPA), that is composed of seven diamond producers: Alrosa, De Beers, Dominion, Lucara, Murowa Diamonds, Petra and Rio Tinto.

‘GMA’ and the Consumer Who Bought an Undisclosed Lab-Grown Diamond

It was a story that the industry had long feared, but perhaps knew would eventually come.

The unwelcome wake-up call aired on Thursday’s episode of Good Morning America. The ABC news show ran a segment featuring a consumer who bought a diamond that she thought was natural, but turned out to be lab-grown.

According to the show, Molly Carlson bought her diamond engagement ring at an unnamed “jewelry store at a local mall.”

“I took it to another jewelry store, and I said, ‘What can you tell me about my ring?’ ” she said. “And they told me, ‘Well, I can tell you, it’s not a natural diamond.’ ”

“Turns out, Molly’s dream diamond was actually a diamond created in a lab,” said reporter Amy Robach.

“[The salesperson mentioned] the style, the, color, and the clarity,” said Molly’s fiancé, Scott Long. “But never once, this is lab.”

The show pointed out that that the Federal Trade Commission’s Jewelry Guides say that retailers must clearly and conspicuously tell customers if their diamond is man-made. full article

The Lab-Grown Diamond Patent Battle Is Heating Up

To grow diamonds, you need a lot of heat and pressure. And now, we’re seeing that on the legal front as well.

On Friday, the High Court of Singapore ruled that diamond grower IIa Technologies had infringed on a patent (SG 872) held by De Beers’ industrial diamond division, Element Six.

The patent relates to the production of diamonds using the chemical vapor deposition method.

In her 199-page ruling, which followed a trial and four years of litigation, Justice Valerie Thean ordered IIa—whose diamonds are sold by sister company Pure Grown Diamonds—to cease producing any items that infringe on Element Six’s CVD growing patent. read article

WD Sues 6 Lab-Grown Diamond Companies Over Patents

On Thursday, the Carnegie Institution of Washington and M7D Corp.—the legal name of WD Lab Grown Diamonds—sued six created-diamond companies for allegedly violating Carnegie’s patents for growing and enhancing diamonds with the chemical vapor deposition method.

The suits, filed yesterday in Southern District of New York federal court, target three pairs of related lab-grown diamond companies: Pure Grown Diamonds, based in New York City; IIa Technologies, based in Singapore; Fenix Diamonds, based in New York City, Mahendra Brothers, based in India; and ALTR Inc. and R.A. Riam Group, both based in New York City.

The three suits, which use similar language and make similar claims, allege that that the companies are infringing on two Carnegie Institution patents, to which M7D holds the license.

The first, patent number 6,858,078, issued in February 2005, lays out a method for producing CVD diamonds using a microwave-plasma process. The second, patent, RE41189, reissued in April 2010, covers a method for improving a diamond’s visual qualities using high-pressure, high-temperature treatment, a process sometimes called annealing. Diamonds grown with chemical vapor deposition that haven’t been treated are known as “as-grown.”

According to the three complaints, the patents at issue are “well-known in the lab-grown diamond industry and in particular are well-known by lab-grown diamond manufacturers, importers, and sellers.”

The plaintiffs seek an injunction against the production of any allegedly infringing products and that M7D and Carnegie receive a “reasonable royalty” from any past sales of infringing products.

“We are very serious about protecting our rights and our investment,” WD’s chief executive officer Sue Rechner, who was appointed in September, tells JCK. “The decision to start litigation is not one any company takes lightly. It’s typically a last resort. We don’t want to go into litigation, but if we must, we must. We are adamant that our intellectual property be respected.” more

How to Talk (Correctly!) About Lab-Grown Diamonds

When it comes to lab-grown diamonds, you don’t want to get too creative with language. Here’s a refresher on the lingo (and legalities).

In 2018, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) concluded a major overhaul of its Jewelry Guides, including its recommendations on lab-grown diamonds. Many in the lab-grown community, with some validity, hailed the changes as a major victory.

And yet, in the months since, some have gotten “creative” with their interpretations of the new Guides, says Jewelers Vigilance Committee (JVC) president and CEO Tiffany Stevens. A year after the overhaul, the FTC sent eight companies that sell lab-grown diamonds and diamond simulants letters about their marketing, warning their advertisements could possibly “deceive” consumers.

Which is why it’s important to review what the FTC Guides do—and don’t—say:

Disclosure is still required.

In perhaps the most commented-upon change, the FTC removed the word natural from the definition of a diamond. “It is no longer accurate to define diamonds as ‘natural’ when it is now possible to create products that have essentially the same optical, physical, and chemical properties as mined diamonds,” the FTC wrote, explaining the change.

That has led some to insist that the FTC has declared “a diamond is a diamond.” While that’s a possible interpretation of the change, the commission never used that particular wording. Under the new FTC Guides—just like the old ones—the unadorned word diamond can still refer only to a natural, mined gem. That means disclosure remains a requirement for non-natural diamonds.

“Marketers still need to make those disclosures [if they are not selling] a mined diamond,” says Reenah L. Kim, staff attorney for the FTC’s enforcement division, who worked on the revamp. Furthermore, the disclosures need to be clear and conspicuous—and the closer the disclosure comes to the claim, the better.

“Some advertisers reveal the true nature of their products behind vague hyperlinks, in an FAQ section, or on an ‘education’ page,” wrote the FTC in a June blog post. “That won’t do. Consumers could easily overlook the information because it’s not close to the product description.”

Marketers even have to be careful on social media. If the only descriptor comes in a hashtag (#labgrown), that could be misleading, the FTC says.

The FTC recommends three descriptors for lab-grown diamonds.

So how should companies describe lab-grown diamonds? The FTC recommends the terms laboratory-grown, laboratory-created, and [manufacturer name]-created. It has okayed use of the word cultured, but manufacturers need to use other descriptive or qualifying language.

The term synthetic was once on that list of recommendations, but it was removed with this revision. However, contrary to some assertions, synthetic hasn’t been prohibited; some lab-grown companies currently use it in their marketing.

The new guides do give marketers leeway to use other descriptors “if they clearly and conspicuously convey that the product is not a mined stone.” But that doesn’t mean marketers can call their diamonds whatever they want. For instance, in the warning letters it sent out in June, the FTC cautioned against using the descriptors aboveground and real diamonds created in America, which it felt “[do] not clearly and conspicuously disclose that the diamonds are laboratory-created.”

“As a federal agency, [the FTC is] always balancing consumer protection against free speech,” Stevens said on “The Jewelry District,” JCK’s podcast. “They wanted to give a little more of that free speech breathing room. Their line of thinking is, ‘Let’s open this up. And if anyone steps over the line, we’ll slap them down.’ Which they did.”

Stevens thinks the safest bet is that companies stick to the three recommended descriptors. “That fourth category is a little unknown,” she says.

Simulants are different from lab-grown diamonds.

The FTC—as well as the world of gemology—has always been clear that a simulant, or simulated diamond, may look like a real gemstone but has a different chemical composition. Moissanite, cubic zirconia, and YAG are examples of simulants. Partial-diamond hybrids are also considered simulants.

A lab-grown diamond is chemically the same as a natural diamond, but it’s grown by a machine rather than beneath the surface of the earth.

In its warning letters, the FTC charged that some marketers were deliberately fudging the difference between the two. It warned companies to “avoid describing [simulants] in a way that may falsely imply that they have the same optical, physical, and chemical properties of mined diamonds.”

Among the descriptors the FTC singled out in its warning letters: lab-created DiamondAura and contemporary Nexus diamond. It has said that the terms lab-created and lab-grown should be used only for products that have “essentially the same optical, physical, and chemical properties as the stone named.” For simulants, it recommends the terms imitation or simulated.

You can still call natural diamonds natural diamonds.

Another common misconception is that the FTC is not allowing mined diamonds to be called natural or real. Those terms are still allowed, but only for diamonds that come from the earth.

The FTC did, however, warn that those terms can’t be used in a misleading context. “It would be deceptive to use the terms real, genuine, natural, or synthetic to imply that a lab-grown diamond (i.e., a product with essentially the same optical, physical, and chemical properties as a mined diamond) is not, in fact, an actual diamond,” it wrote.

Don’t say lab-grown diamonds are eco-friendly.

The FTC’s Green Guides have long warned against what it calls “general environmental benefit” claims, like eco-friendly and sustainable. read more

Why a Few Lab-Grown Diamonds Temporarily Change Color

Laura Sipe couldn’t believe her eyes. In February, the owner of J.C. Sipe Jewelers in Indianapolis was readying an I-color lab-grown diamond for a customer. She had always heard that lab-growns fluoresce differently under ultraviolet light, so she decided to take out her UV lamp and check for herself.

When she removed the stone, it was no longer an I. It was gray. And she “freaked out.”

She called up her vendor, who was just as surprised. “One person in the office said she had heard of something like this. She said the diamond turned purple and then it reverted back.”

Sipe’s diamond indeed returned to its original color the next day. She still told the vendor to take it back.

If a customer saw that, “that would freak everyone out,” she says. “Including us.” She hasn’t had that happen to any stone since.

What brings this up is this week’s announcement that Gemological Science International saw something similar at its lab this summer.

A 2 ct. diamond grown with the chemical vapor deposition (CVD) method transformed from near-colorless to slightly blue (pictured) after a few minutes’ exposure to short-wave UV radiation in a DiamondView machine.

“It was a dramatic change,” says chief information officer Nicholas DelRe. “I thought I was seeing things.”

The diamond retained the blue tinge when it was tucked into parcel papers and only returned to its original hue after two and a half hours in the sun. (Typically, the color reverts after about a half hour of exposure to sunlight.)

Here to stay: what you need to know about lab-grown diamonds

Lab-grown diamonds are disrupting the jewellery industry with their sustainability credentials and prices. Here's what you need to know.

29 May 2019 by RACHAEL TAYLOR

What are the benefits of lab-grown diamonds?

As well as significant savings that allow you to reduce your budget or supersize your diamond, part of the allure of lab-grown is a supply chain that promises no human rights violations and less environmental damage. Though a recent report – funded by a collective of diamond miners – has suggested that the high temperatures required to create lab-grown diamonds cause a larger carbon footprint than mined diamonds, prompting the US Federal Trade Commission to send letters to eight companies warning them off describing the gems as eco-friendly. more...

Is There a Resale Market for Lab-Grown Diamonds?

Last week, at the urging of a commenter, I looked into Kay’s and Jared’s policy for lab-grown diamond upgrades and trade-ins, now that both of those chains are selling them. Suffice it to say, it’s not the same as for naturals. Here’s Jared’s:

Our diamond trade-in and upgrade services allow you to take any diamond jewelry (excluding lab-created diamonds) you no longer wear and trade it in for a brand new one.

Kay’s site has similar language. And so does one of the biggest lab-grown diamond sellers online, Brilliant Earth.

Lab-grown manufacturer Diamond Foundry has traditionally touted its “forever 100% value guarantee”, which “guarantee[s] the value of your diamond forever” with a “free lifetime upgrade.” At press time, JCK could not find the guarantee still listed on its site. The company did not respond to requests for comment about the guarantee’s current status.

This is a thorny issue for the lab-grown diamond world. Given that technology cheapens over time, and created-diamond production isn’t limited by nature, most believe that synthetic prices will drop. In fact, that process has already started, with prices falling over the last year despite a clear spike in demand. (Natural diamond prices have fallen recently, too, though not as much.) Last December, Diamond Foundry announced that it was setting its diamonds at 55% below the Rapaport list. A vendor just approached me on LinkedIn, promising prices 78%–89% below Rap.

Retail prices are falling, too. Analyst Paul Zimnisky estimates they have dropped an average of 20%–30% since the beginning of the year. In January, a 2.01 ct. J SI2 very good–cut lab-grown with an IGI report sold for $6,800 on Brilliant Earth. Recently, a lab-grown with similar specs was being sold on the site for about $3,000.

Which may explain why some sellers are skittish about trade-ins. Though not all are.

Both Ada Diamonds and MiaDonna offer lab-grown upgrades, though they require the purchaser spend a certain price on the new stone—one and one-half times the original in Ada’s case and two times in MiaDonna’s. That isn’t unusual; many traditional sellers have similar policies.

And while it seems an exception, Wisconsin chain Kesslers Diamonds offers the same trade-in policy for lab-growns as it does for naturals—with no minimums.

If the approaches here seem all over the map, they point to a larger issue: Do lab-grown diamonds have resale value? Many in the mined world maintain they don’t.

There is a secondary market for lab diamonds, though it’s still a small one. (Which makes sense, as the category is still small.) Ada Diamonds has had a buyback program since May 2018. This year saw the launch of a somewhat-mysterious site, We Buy Lab Diamonds. And, of course, you can sell anything on eBay.

|

||||||||||||||

Lab-Grown Diamonds Get Ready for Their Eco Close-Up

Six lab-grown diamond companies and retailers have signed up for a pilot program that will audit their environmental, social, and governance performance against preset criteria.

If they pass, their diamonds will be certified by SCS Global Services as sustainably grown, though it’s possible that label will change.

Only individual diamonds will bear the certification, after they have been tracked and traced from grower to the retailer. So, for example, it’s possible a ring’s center stone will carry the the SCS certification, while its side stones won’t. (Just like a center stone sometimes carries a GIA report, while its side stones don’t.)

The pilot, commissioned by the newly formed Lab-Grown Diamond Council, will involve four growers—Green Rocks, Goldiam USA, Lusix, and WD Lab Grown—as well as two retailers, Helzberg Diamonds and Swarovski.

The news comes after the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) in April warned eight lab-grown diamond sellers against using general environmental benefit claims, like eco-friendly and sustainable, which are prohibited by the the agency’s Green Guides.

Interestingly, none of the lab-grown diamond sellers that were cautioned by the FTC are participating in the pilot program. In fact, most of the participating companies have shied away from making eco claims in the past.

“These are companies that want to do the right thing,” says Stanley Mathuram, vice president for SCS, which has also worked with Brilliant Earth and the Responsible Jewellery Council. “The message they are giving now is, ‘We support sustainability, and here are our practices to prove it.’ This won’t be just about how these companies compare to mined diamonds. It’s about each company’s own practices and how they measure up to a transparent standard.”

While Diamond Foundry has been certified carbon-neutral by Natural Capital Partners, this new standard goes beyond that toward “climate neutrality,” Mathuram says.

“It’s not just that we measure your electrical footprint and then you buy offsets,” says Mathuram. “It may be looking at ways to reduce electricity use. This is going beyond carbon-neutral and looking at a multitude of issues. We will also be looking at black carbon, ozone, and methane, and other pollutants that are hot-button topics for climate. We are talking about water, we are talking about solvents, we are talking about chemicals.”

It will also monitor the companies that cut the diamonds and make sure they adhere to existing labor and safety standards. read entire article

Diamond Foundry Signs Power-Full Factory Deal

On June 6, San Francisco gem grower Diamond Foundry inked a deal with a Washington state public utility that will enable its “megacarat” production facility to operate at full capacity by March 2020.

The agreement with the Chelan County Public Utility District (PUD) calls for the construction of a new energy substation that will meet the Wenatchee, Wash., facility’s power needs.

Located in a former fruit warehouse, the facility is expected to grow as many as 1 million carats a year at full capacity. The company also plans to keep growing diamonds in San Francisco.

A joint statement provided a rare glimpse at the amount of power that’s needed to grow diamonds in a lab. The factory will require up to 19 megawatts of power—about what’s used to power an estimated 14,250 to 19,000 American homes, according to California’s department of energy, or, by another calculation, about 11,000 homes in the Pacific Northwest.

The factory’s energy mix will be 98.46% hydropower, with less than 2% of energy from other sources, says Kimberlee Craig, PUD spokesperson.

Transitioning to mostly hydropower will help the company maintain a zero-carbon footprint, the statement said.

As far as other possible ecological impact, the company declined to estimate the factory’s anticipated water usage. “We do not have that information,” says director of public relations and communications Ye-Hui Goldenson.

The PUD lacked the capacity to meet Diamond Foundry’s power needs at its location, requiring the construction of the substation. While that typically takes 18 months, this project is slated to be completed in less than a year because of the factory’s anticipated economic benefit to the local community: It’s expected to bring between 35 and 50 jobs to the area.

“We are a customer-owned utility,” explains Craig. “We are following the direction of our customer-owners, who want us to use our resources to help support the economy.”

When it publicly debuted in 2015, Diamond Foundry announced it had raised $100 million from a range of investors, including actor Leonardo DiCaprio, a group of Silicon Valley billionaires, and firms such as Obvious Ventures. more

The new created-diamond battle may be over intellectual property.

byROB BATES.

In an interview this week, executives at WD Diamonds said they believe that certain competitors are infringing on the company’s licensed patents for growing diamonds using chemical vapor deposition (CVD)—and they might take some retailers to court over it.

Since 2011, WD has licensed the diamond-growing technology developed by the Carnegie Institution of Washington, which has an ownership stake in the company.

“What Carnegie did is they established the conditions that you could [grow diamonds] to a reasonable size,” says WD president and founder Clive Hill. “That is patented. We [believe] that you cannot grow CVD outside those conditions.”’

Carnegie’s portfolio of patents also involve post-growth treatment of CVDs using annealing.

While WD has sent warning letters in the past, Hill says it is now taking its efforts to a new, “more significant” level.

“We have sat down and assessed possible costs,” says Hill. “If we have to end up in court, we will end up there.… We have spent a lot of money on this. We are working with [law firm] Perkins Coie. Within a very short period of time we will start some action with some retailers.”

Among the companies it has in its sights: big retailers, manufacturers of growing equipment, and a few smaller players.

“Hopefully we can pick one or two, and people will cooperate with us a bit better,” he says. “We want to work with people. That is our modus operandi. But we want it to be fair. I don’t think that’s unreasonable. We think that retailers, particularly the significant retailers, will want to make sure that happens.”

The company is now able to pursue this avenue because of the capital infusion it received from Detroit-based private equity firm Huron Capital Partners .

Huron senior partner Michael Beauregard says that WD isn’t trying to limit supply in the market and that it will consider licensing or other arrangements.

“What we would like to do is supply those retailers that we haven’t been supplying,” he says. “The goal is not to create hostilities. The goal is to be able to sell this company’s technology to more customers. There are several retailers that are good and viable customer prospects for this company that have chosen some or part of their product flow to come from parties that have been infringing, in our opinion, on one or more of the patents. They are going to be made aware of that.”

The company is initially targeting retailers, rather than the companies that produce the diamonds, because “we can’t necessarily trace diamonds back to the source,” says Michael Zukas, vice president of private equity for Huron and a WD director. “But we can buy from a retailer and test those diamonds from the retailers and [allege], ‘this is a violation.’

“We have invested in our partnership with Carnegie and the technology that we are licensing,” he says, “and we want to make sure that the playing field is fair and we want to make sure the investment is protected.”

While WD stayed mum on possible targets, JCKreached out to other CVD diamond producers for comment. Diamond Foundry chief executive officer Martin Roscheisen responded via email: “We have invested years of research and development to take the technology for growing high-quality diamond to a distinctly new level. Our proprietary intellectual property stands on its own.” Singapore-based IIA Technologies, which is currently in a patent dispute with Element Six, did not return a request for comment. The agreed purchase of Scio Diamond has suggested that other companies are infringing on itspatents. more

by ROB BATES

Last month, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) shocked the industry by sending out warning letters to eight sellers of lab-grown diamonds and diamond simulants.

The move received a lot of attention as it’s unusual for the FTC to do any kind of enforcement of its Jewelry Guides—never mind sending letters to eight jewelry companies at once.

Letters from the FTC to the Lab Grown Diamond Sellers

In response to a Freedom of Information Act request, JCK recently received the eight unredacted letters, all signed by James A. Kohm, the associate director of the FTC’s division of enforcement. The FTC had previously posted a redacted letter.

Three of the letters were sent to companies that exclusively sell lab-grown diamonds—Ada Diamonds, Diamond Foundry, and Pure Grown Diamonds—and the other five were sent to companies that sell diamond simulants—Agape Diamonds, Diamond Nexus, MiaDonna & Co., Stauer, and Timepieces International. Some of the simulant sellers, including MiaDonna and Stauer, also sell lab-grown diamonds.

The letters to the three lab-grown diamond companies advised that sellers of man-made gems should clearly and conspicuously disclose their stones’ origin. The Diamond Foundry and Pure Grown letters cautioned against using non-FTC-recommended terminology, such as “real diamonds created in California” and “above Earth diamonds.”

Kohm acknowledged in the letters that the companies all had portions of their websites that disclosed that their diamonds did not come from a mine. But “consumers could easily overlook” that, he said. Two of the letters also suggested that solely including a #labgrown hashtag may not be considered sufficient disclosure in a social media post.

The FTC also cautioned the companies not to make “unqualified general environmental benefit claims”—such as using terms like environmentally friendly and sustainable—”because it is highly unlikely that they can substantiate all reasonable interpretations of these claims.”

While there are differences of opinion on the environmental impact of man-made versus mined diamonds, the FTC does not seem to be endorsing any side of that argument. It is simply cautioning companies against using those terms and making those broad overarching claims.

Ada Diamonds said it had settled the matter. Diamond Foundry did not return a request for comment says it “prides itself” on being a lab diamond producer that “has worked collaboratively with the FTC for years.” Pure Grown Diamonds declined comment.

The letters to the five simulant sellers said that retailers of those stones should “avoid describing their products in a way that may falsely imply that they have the same optical, physical, and chemical properties of mined diamonds.” (Simulants are look-alikes, such as cubic zirconia, which do not have the same chemical makeup as diamonds, whether natural or lab-grown.)

The letters mentioned Agape’s use of its diamondslabcreated.com as its web address; Diamond Nexus’ use of contemporary Nexus Diamond; Stauer’s use of lab-created DiamondAura; and Timepieces International’s use of diamondeau.

As with the lab-grown companies, Kohm’s letter acknowledged that the companies’ sites have sections that identify the products as simulants. But he again noted that consumers might overlook them.

The letters to the simulant companies, except for Timepieces, also cited their environmental benefit claims.

Stauer president Michael Bisceglia says his company is in the process of changing its site.

“We think the FTC comments were helpful and more than fair,” he says. “We sell mined diamonds, lab diamonds, and diamond simulants, and it was helpful to have that additional clarity.”